During the 1920’s and 1930’s, the small town of Speculator New York, population 261 in 1930 and 345 in 2019, was often abuzz with thousands of sports enthusiasts each weekend. While the village today claims a reputation as being an “All-Seasons Vacation Land,” these visitors were not there to hunt or fish, nor were they there to partake in the winter activities of skiing or snowmobiling. Instead, these spectators were there to watch world-class, heavyweight boxers prepare for some of the most iconic boxing matches in the history of the sport. But why Speculator, a remote, Adirondack Mountain wilderness town that was 30 miles from the nearest railroad station in Northville? And why at a time when vehicles were rudimentary and road conditions were crude, which allowed cars to go no faster than 35-40 miles per hour?

The reason centered around a relationship that was formed by two young United States Marines, named William (Bill) Osborne and Gene Tunney, serving in France, during WWI. Osborne, a decorated war hero during the First World War, was the son of Will and Nora Osborne, who were the proprietors of the resort complex of the Osborne Inn and Hotels in Lake Pleasant, New York. Tunney was an aspiring boxer from New York City who had made a name for himself, representing the Marine Corps in the ring, towards the close of the war. Osborne often worked as a corner-man during Tunney’s fights and the two made a pact that would come to fruition several years after the war. That pact was tied to the possibility of Tunney one day competing for the Heavyweight Championship of the world. To better understand the pact and how it would bring boxing notoriety to the Adirondacks, it is important to learn about the life of iconic boxer Gene Tunney.

James Joseph “Gene” Tunney was born in 1897 in Greenwich Village, New York, to Irish immigrants, John and Mary Lydon Tunney. John was a longshoreman who loaded and unloaded boats on the Hudson River. Gene was the second-oldest of seven children, and it was his mother's wish to see him become a Catholic priest. Growing up in Greenwich Village brought its challenges, as the sidewalks were ruled by neighborhood bullies. These bullies were older, heavier kids who targeted the younger children. To compound the problem for young Tunney, he was a good student and was an avid reader. Being regarded as an intellect and being seen carrying piles of books to and from school made him an even bigger target, and he often returned home from school, bloodied because of it. For his 10th birthday, his father bought him a pair of boxing gloves. While his father was an avid professional boxing fan and had done some bare-knuckle, club-fighting in New York City as a teenager, the gloves were not intended to turn his son into a boxer, but rather to allow him to learn how to defend himself. He initially began working out and doing light sparring with his younger brothers, and then on to the local gyms to box with children his own age. It was there that his quickness caught the eye of a local area professional lightweight boxer, named Willie Green, who asked Tunney to spar with him. Despite his small stature of 5’ 10” and 130 pounds, Tunney developed enough boxing skills to be able to protect himself and his siblings. He also excelled at basketball, baseball, swimming, running and handball. During the summer months, he and his friends spent considerable amounts of time around the piers on the Hudson River, where they swam and took interest in the various boats that would parade up and down the river near the docks at West Tenth Street. All the while, he excelled at school and continued to spend vast amounts of time in the school library and on the docks of the Hudson River, where he read books on every subject imaginable. He also took part in theatrical productions at his school and played Antonio in Shakespeare’s "Merchant of Venice." Aware of his family’s financial struggles, at the age of 15, Tunney left school and went to work as an office boy for the Ocean Steamship Company on the Hudson River waterfront, earning $5 a week. He then taught himself how to type and was promoted to mail clerk and received a salary of $11 a week. While he continued to play basketball and participated in local long-distance running, he was starting to envision a career with the Ocean Steamship Company as his path to life-long financial success. In 1913, at the age of 16, Tunney was approached by his former sparring partner, Willie Green, to help him train for his comeback into professional boxing. Tunney was now six feet tall, but weighed a mere 135 pounds, and began once again sparring with Green. Tunney was no match for Green and took a beating in their initial training session. As he laid in bed that night, going over the sparring session in his mind, he determined what he did right and what he did wrong. He anticipated what to expect in the second session and was ready for Green and performed much better. Promoters who witnessed the sparring session approached Tunney and Green and invited them to box in a local Knights of Columbus Smoker. Professional boxing in New York State was illegal at that time, and the local smokers took place secretly in Catholic Church halls and Knights of Columbus clubs. Tunney began boxing in these matches, earning no more than a sandwich and soda after each fight. Over the next two years, Tunney fought in these amateur matches and continued to spar with Green. It was during these sparring sessions that Tunney developed a thinking-man’s approach to boxing. He studied his opponent’s strength and weaknesses in order to be prepared for what to expect when in the cusp of battle with them. He also learned the art of feinting, in which a fighter moves his head to ride with a punch as it hits him, lessening the impact from the strike.

In 1915, Tunney was approached by professional fight promoter, Billy Jacobs, to box in a professional 10-round contest for $25. While the 18 year-old Tunney enjoyed boxing, he had no aspirations of making it his career, as he still envisioned one day becoming the dock superintendent of the Ocean Steamship Company where he could make upwards of $25,000 per year. After some convincing, he took the fight, and on July 2, 1915 he beat seasoned fighter Bobby Dawson for his first official professional win. He would continue to fight professionally and competed in eight more matches from 1915 through February 1917, while continuing to work for the Ocean Steamship Company as his main source of income and focus.

In April of 1917, the United States entered World War I when President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany. Without telling his family, Tunney went to a U.S. Marine Corps recruiting station in Manhattan to enlist. However, he had injured his left elbow in a fall during a basketball game the prior month, and it had not healed correctly. The arm had been immobilized in a plaster cast for five weeks, causing it to become atrophied and shorter than his right arm. This caused him to fail his physical on the grounds that his left arm was deemed partially paralyzed. He then set out on a mission to get the arm healed so that he could try to enlist again. After trying numerous home remedies and massages, it was recommended by his doctor that he take a job outdoors, to further exercise and allow the arm to properly heal. Tunney left his job with the Ocean Steamship Company, where he was making $17 per week, to work in New Jersey as a lifeguard and bouncer at a nearby tavern for the summer. Each morning he would put in several miles of running, and then swim one mile before starting his shift as a lifeguard. When the summer season ended, he was in great shape, but his arm still hurt. He tried to get his old job back at the Ocean Steamship Company, but due to the specter of German submarines threatening ship travel across the Atlantic Ocean, business had fallen off and they no longer needed him. Unable to find work to help support himself and his family, he now weighed 155 pounds and began fighting again as a middleweight, which carried a maximum weight of 160 pounds at that time. Even though his left arm still hurt, he would fight four more times between October 1917 and July 1918. Relying on his right arm, he won each bout, and was making as much as $40 per fight. Tunney felt guilty that he was making as much for one fight as U.S. soldiers were making in a month in risking their lives in France, so he sought an alternative solution to get his arm healed. He found a doctor in Manhattan, who had invented an electrical therapy device to treat the traumatic neuritis on his ailing left arm. He began receiving three treatments per week at a cost of $2 each. During that time, he also found a way to contribute to the war effort by taking a job in Hoboken, New Jersey where he inspected aircraft parts being sent to the war efforts in Europe. After five months of treatments, the arm healed and his doctor assured him that he would now pass the Marine physical. In July of 1918, Tunney passed the physical and was sworn into the United States Marine Corps at a salary of fifteen dollars per month. The following day, he reported for active duty and was sent to Parris Island in South Carolina for basic training. Even though he held an undefeated record in 13 professional fights, nobody in the service was aware of his boxing experience. As far at Tunney was concerned, his boxing career was over. And if he survived the war, he hoped to one day return to the Ocean Steamship Company when the public again had confidence in the safety of ship travel.

During basic training, a drill instructor bullied the recruits to the point of provoking them into boxing him. Many recruits would fall victim to his treatment and attempted to take on the instructor after being humiliated by him. Tunney watched as the much larger instructor, who obviously had some boxing experience, easily beat down the recruits. After pushing Tunney too far one day, he accepted the instructor’s taunts to box him. Having watched the instructor's fighting style several times, he knew what to expect and was easily able to duck out of the way of the instructor’s punches. With the very first punch Tunney threw, he landed it on the instructor’s jaw and knocked him unconscious. The abuse stopped and shortly after the incident, Tunney and his Company D of the 5th Brigade of the 11th Marine Regiment were sent to France. During bayonet training, a fellow recruit who was unaware of Tunney’s boxing background, picked a fight with him. While trying to talk his way out of the confrontation, the challenger struck Tunney, knocking him down. Tunney rose with a left-hook that sent the fellow marine into a ditch. Bystanders were in awe of the strike, and he was forced to admit to his sergeant (who witnessed the incident) that he had previously fought professionally. After two months of training in France, Germany surrendered and the war was officially over on November 11, 1918. Having only been in the Marines for five months, Tunney did not have enough time accrued to be immediately discharged and thus remained in France. To pass the time in the evenings, Tunney attended boxing programs in which servicemen from the local bases competed. On the evening of the base championships, one of the welterweight finalists failed to appear. It was announced that if nobody was willing to stand in for the missing fighter, that the base championship would go to the Army boxer already in the ring. Knowing that he had professional experience, his sergeant urged Tunney to get in the ring to represent the Marine Corps. Tunney initially refused, but was eventually coaxed into getting into the ring with the promise of being relieved from guard duty for the following day, if he fought. Tunney removed his shirt, put on a pair of boxing gloves and entered the ring, wearing long pants and military boots. After two rounds of being subjected to Tunney’s punishing strikes, the Army fighter refused to return to the ring for the third round, thus giving the base championship to Tunney. For the remainder of Tunney’s time in France he continued to box in tournaments, in exchange for "time off" from the monotonous guard duty that most of the soldiers were not very fond of. Over the next few months, Tunney would compete in approximately 20 matches and struck up a friendship with Marine Sergeant, Bill Osborne, who had been wounded badly and had earned the Purple Heart and the Croix De Guerre medal for heroism. After his hospital stay in France, the two men became close friends, and Osborne often worked in Tunney’s corner during his fights.

On April 26, 1919, in front of 14,000 fight fans at the Cirque de Paris in Paris France, Tunney won the light-heavyweight championship of the American Expeditionary Forces boxing tournament, thus earning the nickname “The Fighting Marine.” A few months later, on July 4, 1919, back home in Toledo Ohio, Jack Dempsey became the heavyweight boxing champion of the world when he defeated Jess Willard. Tunney, who now had visions of returning to professional boxing when he returned home, became fixated on the notion of one day fighting Jack Dempsey for the Heavyweight title. According to William Osborne Jr., grandson of Tunney’s corner-man in France, “my grandfather made an offer to Tunney that if he were to one day fight for the heavyweight championship, that he should consider coming up to his family's resort in Lake Pleasant, New York to train in the fresh Adirondack Mountain air. He also touted the fact that his mom was one of the greatest cooks in the world and would provide him with great meals. Tunney accepted the offer and promised that if he ever fought for the World's Heavyweight Championship, that he would come to Osborne’s family's resort to train.”

On August 14, 1919, Tunney received an honorable discharge as a Private First Class and was awarded the Good Conduct Medal. Upon returning home from military service in Europe, Tunney’s parents, while proud of his boxing accomplishments, still clung to the hope that he would become a priest. However, needing work and wanting to fulfill his dream of one day challenging Dempsey for the heavyweight championship, he returned to boxing and fought his next professional fight on December 16, 1919. He now weighed 160 pounds and fought in the light-heavyweight class a total of 15 times in 1919 and 1920, winning all of them. He now held a record of 28 wins and no losses, but often suffered broken bones in his hands due to being handicapped with brittle knuckles and soft hands. To build up strength in his hands, he squeezed a rubber ball all day and night to help strengthen the tendons in his fingers. In January of 1921, he took on a job as a lumberjack with a lumber company in the Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario Canada. He never told anyone that he was a boxer, and from sun-up to sun-down, he quietly took on the heavy work of using axes and saws to strengthen his hands. His hands grew strong and hard, with his fists becoming tough enough to better take the impact of landing his powerful punches. When the lumbering season ended in the spring, he then took a job as a laborer in Poland Springs, Maine. This was to help him further build strength in his hands, wrists and his overall body. Due to his previous hand issues, he developed skill and defense as a boxer. He practiced dodging blows through defensive sparring and also developed a stick-and-move strategy that utilized his excellent left jab. He stayed outside his opponents reach and applied quick counter-punches to keep them off-balance. He was fleet-footed and constantly moved, while always applying rapid-fire jabs. He also utilized body punches as much as head punches. And by studying his opponent’s strengths and weaknesses before and during fights, he became a thinking fighter who turned a boxing match into a game of chess.

With his hands healed and stronger than ever, he returned to the ring on June 28, 1921 and would win eight more fights that year. His big break came in his second fight back when he was signed to fight Soldier Jones on the undercard of the July 2, 1921 Jack Dempsey-Georges Carpentier World Championship bout in Jersey City, New Jersey. After beating Jones with a seventh round TKO, Tunney sat ringside for the main event to watch and study Dempsey’s fighting technique. On January 13, 1922, Tunney defeated Battling Levinsky for the newly created North American light heavyweight championship. On May 23rd of that same year, he would lose the title in a 15-round decision to Harry Greb. This was the first loss of his professional career, and would be his last. He would avenge the loss by taking the title back from Greb in 1923 and beating him in three additional fights. By August of 1924, Tunney now weighed 175 pounds and started competing as a heavyweight, hoping to earn his shot at Dempsey. After 12 wins as a heavyweight between August 1924 and December 1925, Tunney now held a professional record of 74 wins and just 1 loss. After his June 5, 1925 knockout of Tommy Gibbons in 12 rounds, Tunney began campaigning for a heavyweight title fight with Dempsey. While Tunney’s unwavering self-confidence was often considered unrealistic by many in the boxing industry, Dempsey had been unable to knock out Gibbons in a 15-round fight back in 1923. The fact that Tunney was able to knock out Gibbons was used to make the case for giving Tunney his shot at the title.

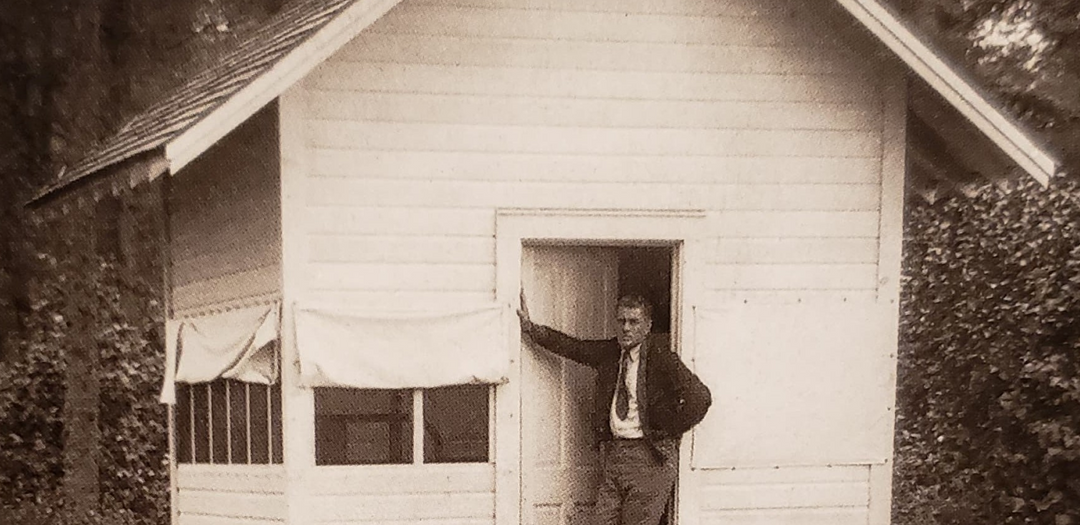

At the age of 28, Tunney was granted the opportunity of challenging Dempsey for the world’s heavyweight Championship, set for September 23, 1926. While the exact location of the fight was not immediately established, Tunney began looking for a quiet and healthy location with no distractions in which to train. He did not like the smoked-filled gyms of his native New York City, and learned during his time as a lumberjack that he enjoyed the solitude of the woods to relax him and to physically train more effectively. Remembering the pact he and his friend Bill Osborne had made seven years prior while in Europe as Marines, Tunney wired Osborne in Speculator and asked him if his offer was still good to come and train at his family’s resort in the Adirondack Mountains. Lake Pleasant had incorporated the year before, changed its name to Speculator and was looking for ways to bring people to town to boost the economy. Days later the two former Marines met in Saratoga, New York to discuss the details of what would be needed by both parties, and it was agreed upon that Tunney would hold his training camp for his challenge of the world heavyweight championship at the Osborne Hotel Resort. An outdoor boxing ring was built on the shore of Lake Pleasant that had a roof over it to protect Tunney from the sun and rain. The sides were left exposed so fans and the press could watch the workouts. And the two hotels and cabins on the Osborne property, as well as other hotels in the area would serve to house those who came to witness the training camp.